OKRs in a Nutshell

OKRs are a method for setting and tracking goals. An objective describes what is to be achieved. The key results state how we accomplish the objective. Let’s say, for example, that the objective is to “increase engagement.” The key results might then be “simplify user journey A” and “enhance feature alpha.”

OKRs can be used to create cascading goals—goals that are systematically linked. This is done by using higher-level key results as lower-level objectives, as the following example shows.

In figure 1 above, the key result “simplify user journey alpha” becomes an objective with two new key results, “remove user journey step two” and “improve performance by 10%” thereby connecting the two OKRs.

It’s worthwhile to note that OKRs were originally invented by Andy Grove at Intel in the 1970ies to facilitate “excellent execution,” that is, to help people set hard, measurable goals and to be able to clearly determine if these have been met. And that’s exactly how I experienced OKRs when I worked at Intel in the late 1990ies.

Goals in Product Management

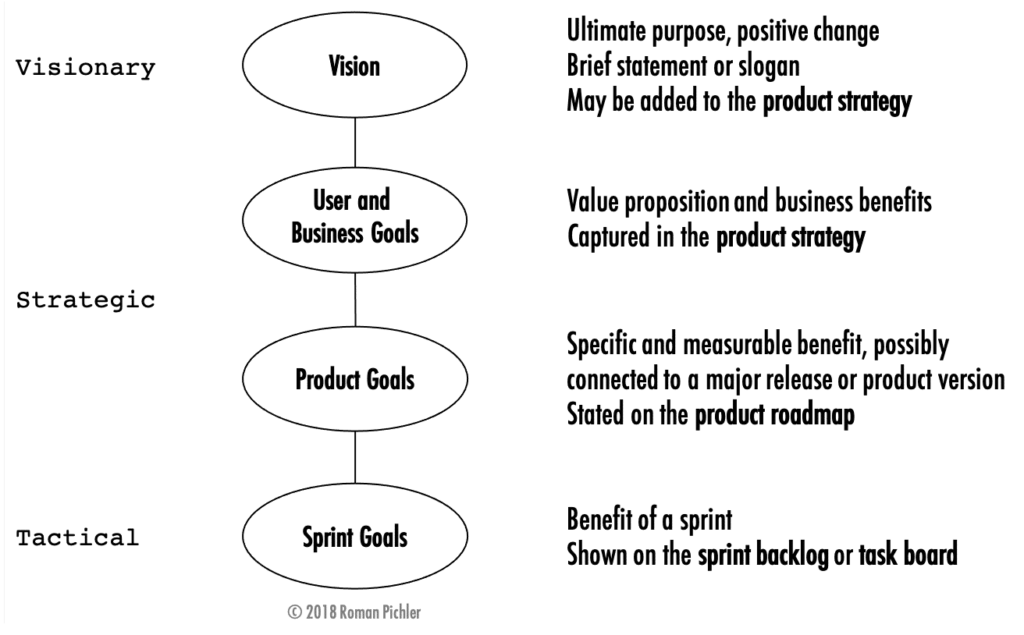

As I explain in my book How to Lead in Product Management, setting the right goals is crucial to align stakeholders and development teams and to achieve product success. Does this mean that there is a natural fit between goals in product management and OKRs? In order to answer this question, let’s look at a set of product management goals. Figure 2 below shows the goals I recommend.

Figure 2 contains a set of cascading goals: vision, user and business goals, product goals, and sprint goals. The vision guides the user and business goals, which are contained in the product strategy. The user and business goals help select the right product goals, which I capture on the product roadmap. A product goal, finally, helps determine the right sprint goals.

At the same token, a sprint goal is a step towards a product goal; achieving a product goal helps you make progress towards the user and business goals; and the latter two finally help you move closer towards your vision. (For a more detailed explanation of the goals above, please see my article “Leading through Shared Goals,” and if you would like to learn more about goal setting in product management, then check out my book How to Lead in Product Management.)

Let’s now explore how the goals in figure 2 can be captured as OKRs.

Capturing Product-related Goals as OKRs

Say that I’d like to offer a product that helps people eat more healthily. I could then capture the goals shown in the picture above as OKRs in the following way:

There are three things in figure 3 above that I’d like to bring to your attention: First, the top-level OKRs describe vision and product strategy. The vision is the objective, and the product strategy is expressed by the key results.

Second, I have derived the product goal objective from the first and third key result of the top-level objective (as illustrated by the grey arrows). I have also used the first key result of the second objective to determine the third objective. This creates a set of cascading OKRs. I wasn’t able, however, to reuse higher-level key results as lower-level objectives, as shown in figure 1.

Third, the second OKRs are the equivalent of the first entry on a goal-oriented product roadmap. If you want to work with a roadmap that looks further ahead, you will have to add additional OKRs to the ones in figure 3.

Should You Use OKRs for Your Product?

To answer this question, let’s consider some major benefits and drawbacks of applying OKRs in product management, starting with the positives:

- Consistency: Using OKRs means that all goals adhere to the same format. This can be particularly helpful when OKRs are widely used in the organisation and the stakeholders and development team members are familiar with the method.

- Validation: Coupling objectives with key results can help you tell if and when a goal has been met.

- Links: Being able to use key results as new objectives is very useful, even though I was not able to take advantage of it in the sample OKRs in figure 3.

But I also see the following drawbacks:

- Lack of visualisation: Using OKRs to capture goals leads to a rather text-heavy approach. This feels like turning back the clock and not taking advantage of the visual product management tools developed in recent years like my product vision board and GO product roadmap or Alexander Osterwalder’s business model canvas. These tools make it easier, though, to understand, validate, and evolve a product strategy, product roadmap, and business model respectively.

- Overuse: Objectives should be significant, concrete, and action-oriented, writes John Doerr in his book Measure What Matters. And Andy Grove pointed out that key results should be “so specific that a person knows without question whether he has completed them and done it on time or not.” While you can use OKRs to capture a vision and strategy—as I did in figure 3—it seems to me like shoehorning them into a format they don’t naturally fit into. I personally find that OKRs are best used for what they were invented for: to facilitate execution.

Should you now use OKRs? I recommend applying them if they help you set and track the relevant goals and if the they can be easily understood by the stakeholders and development teams. If you are in doubt, experiment with the goal-setting approach and see how it works for you. Make sure, though, that you stay in charge of the product and don’t allow powerful stakeholders to dictate product OKRs to you.

Have you used OKRs to manage your product? If so, I’d be love to hear your experiences. Please share them in a comment below.

The post OKRs in Product Management appeared first on Roman Pichler.

OKRs in Product Management posted first on premiumwarezstore.blogspot.com

Thanks for this information. Cash For Cars Adelaide.

ReplyDelete